Sydney, Australia – Ju-rye Hwang grew up assuming her parents in South Korea were dead and that she was alone in the world after being adopted to North America at about six years of age.

That was until a phone call from a journalist in Seoul turned her world upside down.

Recommended Stories

list of 4 itemsend of list

“He told me that I was not an orphan,” Hwang said.

“And it was most certain that I was illegally adopted for profit,” she said.

The journalist went on to tell Hwang about the notorious Brothers Home institution in South Korea, a place where thousands had endured horrific abuse, including forced labour, sexual violence, and brutal beatings.

Hwang discovered that she had spent time at the institution as a child, before being offered for overseas adoption.

The journalist also explained how his investigative team had uncovered a file from the home’s archives containing a list of international adoptions, and among the clearly printed names was that of her adoptive mother.

Hearing “the truth”, Hwang said, “made me break down and lose my breath”.

“I felt physically ill,” she told Al Jazeera.

“I believed that my parents were not alive.”

‘Beggars don’t exist here’

Hwang is now a successful career woman in her mid-40s. But her origins link back to South Korea during the 1970s and 80s, when government authorities in the rapidly industrialising nation cracked down brutally on those considered socially undesirable.

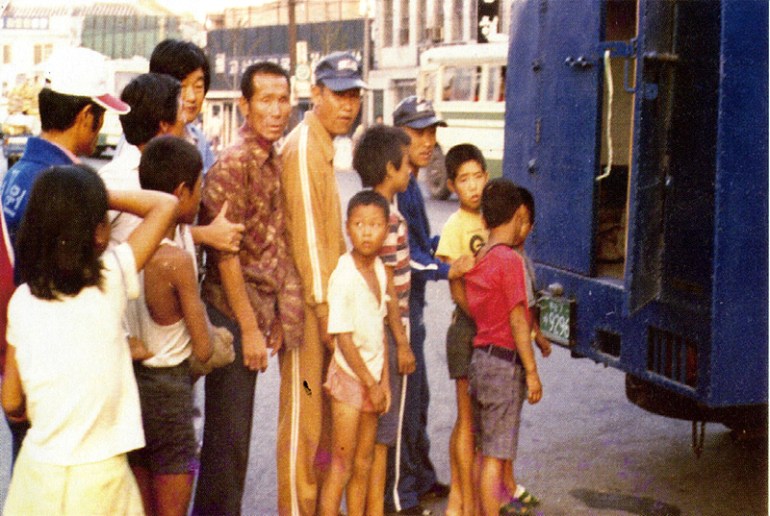

Kidnapping was rampant among the children of the poor, the homeless and marginalised who lived on the streets of Seoul and other cities.

Children as well as adults were abducted without warning, bundled into police cars and trucks and hauled away under a state policy aimed at beautifying South Korean cities by removing those designated as “vagrants”.

By clearing the streets of the poor, South Korea’s government sought to project an image of prosperity and modernity to the outside world, particularly in the lead-up to the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul.

The then-president and military leader, Chun Doo-hwan, famously boasted of South Korea’s economic success when he told reporters: “Do you see any beggars in our country? We have no beggars. Beggars don’t exist here.”

The president’s push to “cleanse” the streets of the poor and homeless combined toxically with a police performance system based on the accumulation of points that propelled a surge in abductions.

At the time, police earned points based on the category of suspects they apprehended. A petty offender was worth just two performance points. But turning in a so-called “beggar” or “vagrant” to institutions such as the Brothers Home could earn an officer five points – a perverse incentive that prompted widespread abuse.

“The police abducted innocent people off the streets – shoe shiners, gum sellers, people waiting at bus stops, even kids just playing outside,” Moon Jeong-su, a former member of South Korea’s National Assembly, told Al Jazeera.

Brothers Home of horrors

Located in the southern port city of Busan, Brothers Home was founded in 1975 by Park In-geun, a former military officer and boxer.

It was one of many government-subsidised “welfare” institutions across South Korea, established at that time to house the homeless and train them in vocational skills before releasing them back into society as so-called “productive citizens”.

In practice, such facilities became sites of mass detention and horrific abuse.

“State funding was based on the number of people they incarcerated,” said former Busan city council member Park Min-seong.

“The more people they brought in, the more subsidies they received,” he said.

At one stage, up to 95 percent of the Brothers Home’s inmates were delivered directly by police, and as few as 10 percent of those confined were actually “vagrants”, according to a 1987 prosecutor’s report.

In a recent Netflix documentary dealing with the events at Brothers Home, Park Cheong-gwang, the youngest son of the facility’s owner, Park In-geun, admitted that his father had bribed police officers to ensure they sent abducted people to his facility.

![14. Inmates are seen lining up based on their platoons at a sports event at the Brothers Home. [Courtesy of Brothers Home Committee]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/14.-Inmates-line-up-outside-1760682785.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C519&quality=80)

Records reviewed by South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established to investigate historical abuse at Brothers Home and similar centres, revealed that an estimated 38,000 people were detained at the home between 1976 and its closure in 1987.

Brothers Home reached peak capacity in 1984, with more than 4,300 inmates held at one time. During its 11 years of operation, 657 deaths were also officially recorded, though investigators believe the toll was likely much higher.

The home was known among inmates as Park’s “kingdom”. It was aplace where the founder wielded absolute control over every aspect of their lives. The compound had high concrete walls and guards stationed at the towering front gate. No one was permitted to leave without express permission.

Inside, children were forced to work long hours in on-site factories producing goods such as fishing rods, shoes and clothing, while adults were sent out for gruelling manual labour at construction sites.

Their labour was not supposed to be free.

![15. Inmates were subjected to forced labour with no pay. [Courtesy of Brothers Home Committee]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/15.-Labour-work-1760682875.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C519&quality=80)

A 2021 investigation by Al Jazeera’s 101 East investigative documentary series revealed that Park and members of his board of directors at Brothers Home had embezzled what would amount to tens of millions of dollars in today’s value, and which should have been paid to inmates for their work.

Those operating Brothers Home also profited from the country’s lucrative international adoption trade, with domestic and foreign adoption agencies frequently visiting the facility.

Former inmate Lee Chae-shik, who was held for six years at the home, told 101 East that young children, just like Hwang, would simply disappear overnight.

“Newborns, three-year-olds, kids who couldn’t yet walk … One day, all of those kids were gone,” Lee said.

‘The child said absolutely nothing’

Hwang’s intake form at the Brothers Home states that she was found in Busan’s Jurye-dong neighbourhood and “admitted to Brothers Home at the request of the Jurye 2-dong Police Substation on November 23, 1982”.

A black-and-white photo of a very young Hwang is affixed to the top corner of the document, which was seen by Al Jazeera.

Her head is shaved. The form is stamped with her identification number: 821112646, with a line in the comments section: “Upon arrival, the child said absolutely nothing.”

The document notes Hwang’s “good physique”, “normal face shape and colour”, and she is marked on the form as “healthy – capable of labour work”.

At the bottom of the page are Hwang’s tiny fingerprints. She was about four years old at the time.

“That girl is probably scared and in shock,” said Hwang, looking at her own intake document and the picture of her childhood self. Her voice quivering as she spoke, she referred to the “innocent” child who already “has a mugshot”.

![The 'mugshot' photo of Ju-Rye Hwang taken when she arrived at the Brothers Home, as well as her fingerprints, as seen on her intake form, and (right) the signatures of five board directors can also be seen on the form [Courtesy of Ju-Rye Hwang and the Brothers Home Committee]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/Jurye-mugshot-intake-form-1763012951.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C523&quality=80)

“I 100 percent believe that I was kidnapped,” she said. “I know I was never supposed to be at Brothers [Home] as a four-year-old.”

A deeply unsettling discovery was also made in her adoption records: Her name, Ju-rye, was given to her by the home’s director, Park, who named her after the Jurye-dong neighbourhood where police say she was found – the same neighbourhood where the Brothers Home was located.

“I felt violated. I felt sick in the stomach,” she said, recalling the origins of her name.

Growing up, Hwang said she had fragmented memories of South Korea.

Of the few she could recollect, one was of a towering iron gate. The other was of children splashing in a shallow underground pool. For years, she dismissed those memories as probably imagined. Then, in 2022, six years after the call with the journalist, she finally mustered enough courage to investigate her past with the help of a fellow adoptee from South Korea, who had sent her links to a website detailing what the Brothers Home once looked like.

“I was just toggling through the different menus of that website when two vivid images clicked for me,” Hwang said, snapping her fingers.

“The large iron gate – that was the entrance. The underground pool was inside the facility,” she said, matching her unexplained dreams with the images featured on the website.

“It was overwhelming to know that I was not imagining my memories of Korea,” she said.

Hwang would discover that she was kept at the Brothers Home for nine months before being sent to a nearby orphanage, where she was deemed a “good candidate” for international adoption.

In the consultation notes for eventual adoption, the circumstances of Hwang’s so-called abandonment and her admission to Brothers Home, as well as details of her health, were all provided by Park. She was recorded as being in good health, weighing 15.3kg (33.7lb), measuring 101cm (3.3ft) in height, and having a full set of 20 healthy teeth.

Adoption records also described her as an outgoing and well-behaved young girl. Hwang was noted for her intelligence: she could write her own name “perfectly”, was able to count in numbers, recognised different colours, and was also capable of reciting verses from the Bible from memory.

“It seems odd that I had those skills and was well nourished, and yet the police claimed I was a street kid. It just doesn’t add up,” said Hwang, who is convinced she was well looked after before she was taken to the Brothers Home.

In 2021, Hwang submitted her DNA to an international genetics registry and was immediately matched with a fully-related younger brother who had also been adopted to Belgium. She describes her first video call with her long-lost brother as “surreal”.

“For an adopted person who has never had any blood relatives their entire life, coming face-to-face with a direct sibling was jaw-dropping,” Hwang recalled.

“There was no denying we were related,” she said.

“He looked so much like me – the shape of his face, the features, even our long, slender hands.”

Hwang soon learned that she had another younger brother, and both had been adopted to Belgium in early 1986.

Their adoption files, also seen by Al Jazeera, state the brothers were “abandoned” in Anyang, a city about 300km (186 miles) from Busan, in August 1982, about three months before Hwang was taken to Brothers Home.

The timing of her brothers’ adoptions made her wonder whether her parents may have temporarily left her with relatives in Busan, a common practice in Korean families, possibly while they searched for their missing sons, who may also have been taken off the streets in similar circumstances.

Among the few vivid memories that Hwang still retains from her very early childhood, before the Brothers Home, is of a woman she believes may have been her biological mother.

“The only image that stayed with me,” she said, her eyes filling with tears, “is of a woman with medium-length permed hair. I only remember her from the back – I have no memory of her from the front.”

Hwang still holds on to hope that one day she will be reunited with her mother and will discover her true identity.

“I would love to know my real name – the name my parents gave me,” she said.

Truth and Reconciliation

In 2022, South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission declared that serious human rights violations had occurred at Brothers Home. This included enforced disappearances, arbitrary confinement, forced labour without pay, sexual violence, physical abuse, and even deaths.

In the report, the commission stated the “rules of rounding up vagrants to be unconstitutional/illegal”, that “the process of inmates being confined to be illegal”, and “suspicious acts” were discovered “in medical practices and the process of dealing with dead inmates”.

Most children at the home were also found to have been excluded from compulsory education.

The commission concluded that such acts had violated the “right to the pursuit of happiness, freedom of relocation, right to liberty, the right to be free from forced or compulsory labour, and the right to education, as guaranteed by the Constitution”.

The government, the commission said, was aware of such violations but “tried to systematically downscale and conceal the case”.

The commission also confirmed for the first time earlier this year that Brothers Home had collaborated with other childcare centres to facilitate illegal overseas adoptions.

Although many records were reportedly destroyed by the home’s former management, investigators verified that at least 31 children had been illegally sent abroad for adoption. The inquiry eventually identified 17 biological mothers linked to children sent for adoption overseas.

In one case, the commission uncovered evidence of a heavily pregnant woman who had been forcibly taken to Brothers Home. She gave birth inside the facility, and her baby was handed over to an adoption agency just a month later and then sent overseas three months after that.

Investigators found a letter of consent to adoption signed by the mother. But the adoption agency had taken custody of the baby the very day the form was signed, leaving no opportunity for the mother to reconsider or withdraw consent.

The commission noted the high likelihood of the mother being coerced into consenting to the overseas adoption of her child while held inside the Brothers Home, from which she could neither leave nor care adequately for her newborn under the home’s oppressive conditions.

![Park In-keun and his wife, Lim Young-soon, both held executive positions at the Brothers Home, and are said to have wielded enormous amounts of power at the facility. [Courtesy of Brothers Home Welfare Center Incident Countermeasures Committee]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/PARK-IN-KEUN-AND-WIFE.jpg?w=770&resize=770%2C584&quality=80)

Brothers Home’s former director, Park, died in June 2016 in South Korea. He was never held accountable for the unlawful confinement that occurred at his facility, nor did he ever apologise for his role in it.

The commission’s 2022 report strongly recommended that the South Korean government issue a formal state apology for its role in the abuses committed at the home. To date, neither the Busan city government nor the South Korean national police have apologised for involvement in the abuses or the subsequent cover-up, and, despite mounting pressure, no president of the country has issued a formal apology.

In mid-September, however, the government withdrew its appeals against admitting liability for human rights violations that occurred at the facility, following a Supreme Court ruling in March. The move is expected to expedite compensation for a number of the victims who had filed lawsuits against the state over the abuse they suffered.

Justice Minister Jung Sung-ho described the decision to drop the appeals as a “testament to the state’s recognition of the human rights violations [that occurred] due to the state violence in the authoritarian era”.

This week, the Supreme Court further ruled that the state must also compensate victims who were forcibly confined at Brothers Home before 1975, when a government directive officially authorised a nationwide crackdown on “vagrants”.

The court found that the state had “consistently carried out crackdowns and confinement measures against vagrants from the 1950s onwards and expanded these practices” under the directive.

Hwang submitted her case to the commission for investigation in January 2025, and she received an official response confirming that, as a child, she was subjected to “gross human rights violations resulting from the unlawful and grossly unjust exercise of official authority”.

‘Child-exporting nation’

In the decades after the 1950-53 Korean War, more than 170,000 children were sent to Western countries for adoption, as what started as a humanitarian effort to rescue war orphans gradually evolved into a lucrative business for private adoption agencies.

Just last month, President Lee Jae Myung issued a historic apology over South Korea’s former foreign adoption programme, acknowledging the “pain” and “suffering” endured by adoptees and their birth and adoptive families.

Lee spoke of a “shameful chapter” in South Korea’s recent past and its former reputation as a “child-exporting nation”.

The president’s apology came several months after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released another report concluding that widespread human rights violations had occurred within South Korea’s international adoption system.

The commission found that the government had actively promoted intercountry adoptions and granted private agencies near total control over the process, giving them “immense power over the lives of the children”.

Adoption agencies were entrusted with guardianship and consent rights of orphans, allowing them to pursue their financial interests unchecked. They also set their own adoption fees and were known to pressure adoptive parents to pay additional “donations”.

The investigation also revealed that agencies routinely falsified records, obscuring or erasing the identities and family connections of children to make them appear more “adoptable”. This included altering birthdates, names, photographs, and even the circumstances of abandonment to fit the legal definition of an “orphan”.

Under laws in place at the time of Hwang’s adoption, South Korean children could not be sent overseas until a public process had been conducted to determine whether a child had any surviving relatives.

Adoption agencies, including institutions such as the Brothers Home, were legally required to publish public notices in newspapers and on court bulletin boards, stating where and when a child had been found. This process was intended to help reunite missing children with their parents or guardians, and to prevent overseas adoption while those searches were still under way.

However, the commission found that in cases involving the Brothers Home, such notices were published only after formal adoption proceedings had begun. This indicated that the search for an orphan’s relatives was considered a procedural formality rather than a genuine safeguard to protect children who still had family.

The notices were also published by a district office in Seoul rather than in Busan, where the children had originally been reported as found.

The commission concluded that the government had failed “to uphold its responsibility to protect the fundamental human rights of its citizens” and had enabled the “mass exportation of children” to satisfy international demand.

‘Right your wrongs’

Hwang now lives in Sydney, Australia, and her new home is coincidentally the same city where some of the extended family of the late Brothers Home director, Park, now live.

An investigation by 101 East revealed that the director’s brothers-in-law, Lim Young-soon and Joo Chong-chan, who were directors at the Brothers Home, migrated to Sydney in the late 1980s.

Park’s daughter, Park Jee-hee, and her husband, Alex Min, also moved to Australia and were operating a golf driving range and sports complex in Sydney’s outer suburbs, 101 East discovered.

Noting the coincidence of living in the same city as relatives of the late Brothers Home director, Hwang said she believed “things happen for a reason”.

“I’m not sure why, but maybe there’s a reason I’m here,” Hwang told Al Jazeera, adding that if she ever had the opportunity to speak with the Park family, her message would be simple: “Right your wrongs.”

Park’s son, Park Cheong-gwang, admitted in the Netflix documentary series about Brothers Home – titled “The Echoes of Survivors” – that abuses had taken place at the centre.

But he insisted that the South Korean government was largely responsible and that his father had told him that work at the home was carried out under direct orders from the country’s then-President Chun, who died in 2021.

![9. Park In Geun was awarded the Order of Civil Merit medal from President Chun Doo Hwan in 1984. [Supplied by Netflix Korea]](https://www.aljazeera.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/9.-Park-receiving-medal-from-Chun-1-1760683651.jpeg?w=770&resize=770%2C433&quality=80)

Park Cheong-gwang also used his appearance in the Netflix show to issue the first formal apology of any member of his family.

He apologised to “the victims and their families who suffered during that time at the Brothers Home, and for all the pain they’ve endured since”.

Other relatives living in Australia have dismissed the reported abuses at the home.

Hwang said their lack of remorse “was sickening”.

“They’re running away from their history,” she said.

“It’s not only the adoption, but it’s the fact that everything in my life was erased,” she added.

“My identity, my immediate family, my extended family, everything was erased. No one has the right to do that.”